014-Apr 21, 2025

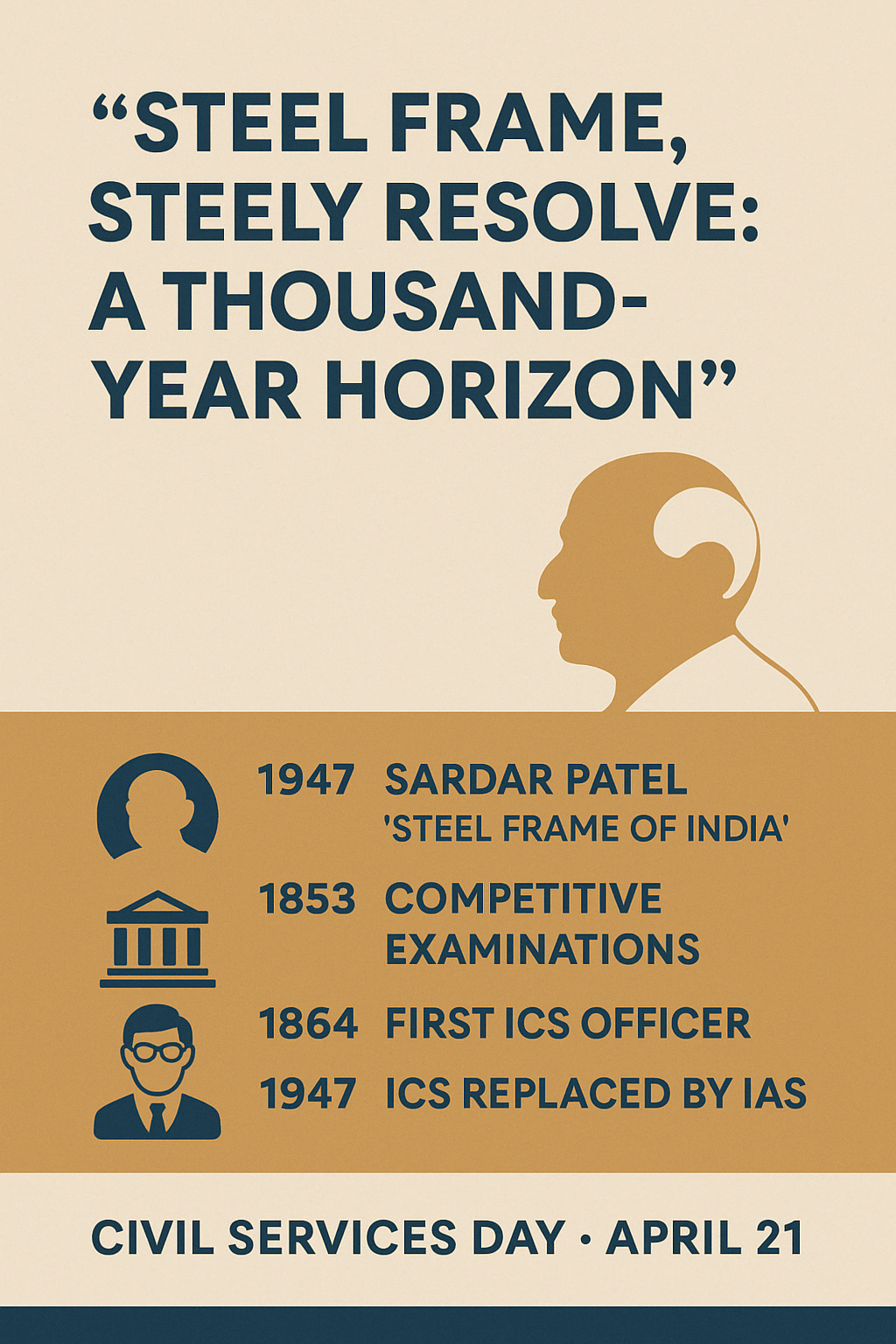

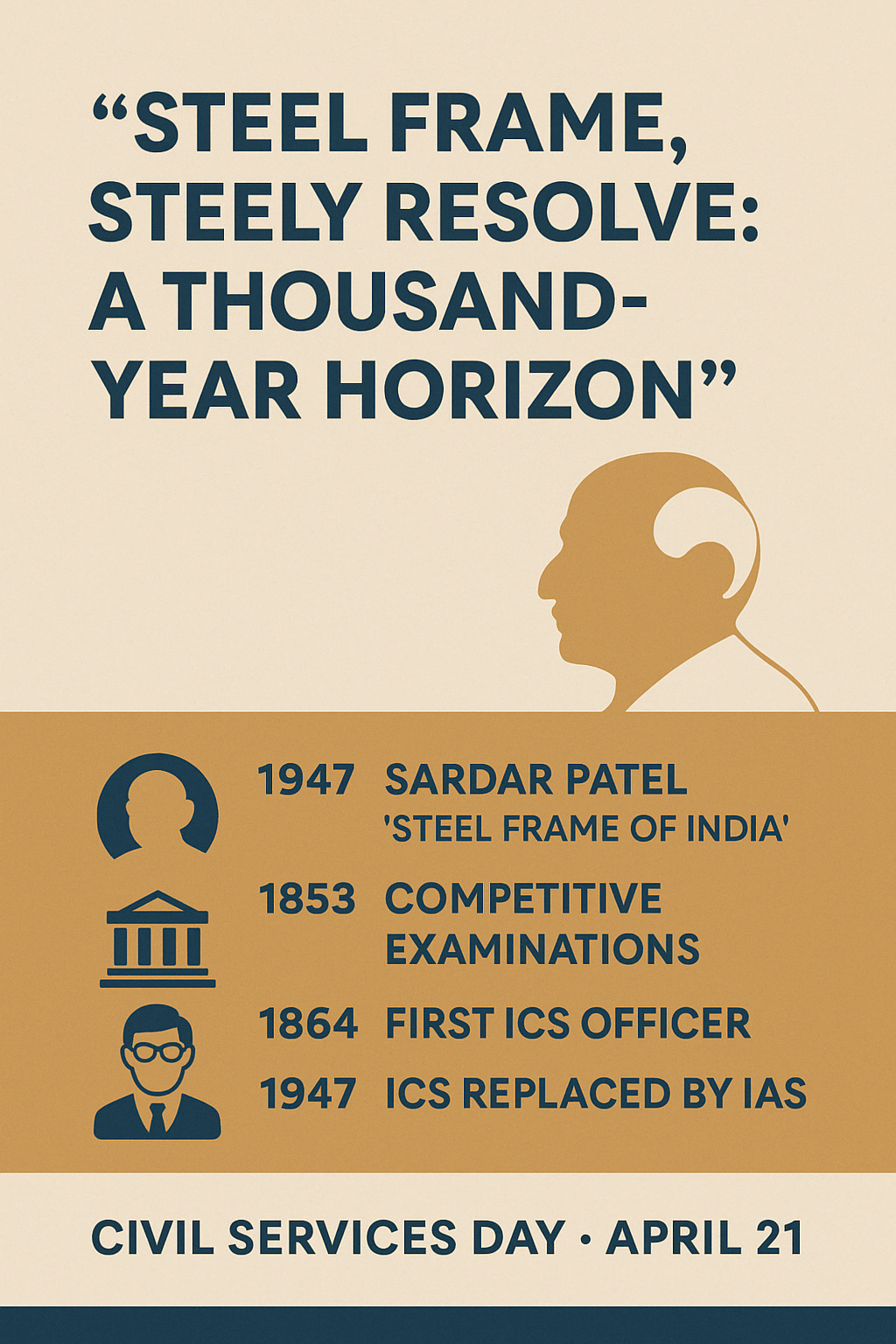

National Civil Services Day 2025 : “Steel Frame, Steely Resolve: A Thousand-Year Horizon”

Most Useful Essay Added at the End

Title: From Colonial Clerks to Constitutional Conscience-Keepers — The Journey of India’s Civil Services is a Reflection of the Nation’s Transformation

🧭 Thematic Focus:

Governance | Public Administration | Indian History

🗂️ Category: GS Paper II – Governance | Essay Paper – Ethics, Legacy & Institutions

🪷 Intro:

On the 17th National Civil Services Day, Prime Minister Modi reminded India’s administrators that today’s decisions echo into the next thousand years. Civil Services are not just mechanisms of implementation — they are moral compasses, forging national destiny. As history reflects, from colonial ink to democratic resolve, the evolution of India’s bureaucracy is a tale of grit, reform, and hope.

✨ Key Highlights:

🏛️ Historic Milestones

- 1853: Competitive exams replaced colonial patronage (Macaulay Reforms).

- 1864: Satyendranath Tagore, first Indian to clear ICS.

- 1922: ICS exams begin in India.

- 1947: IAS replaces ICS post-Independence.

- 1950: UPSC formally constituted.

🗡️ Patel’s Legacy

- 21 April 1947: Sardar Patel calls Civil Services the “Steel Frame of India”.

- Advocated incorruptibility, esprit de corps, and public service as sacred duty.

🌐 Other Civil Services (British Era)

- Imperial Police Service (predecessor of IPS).

- Imperial Forest Service (1867), evolved into modern IFS (1966).

🧠 GS Paper II Mapping:

- Governance Structures: Evolution of Civil Services post-1853.

- Role of Civil Services in Democracy: Ethics, responsiveness, integrity.

- Interventions & Reforms: From Macaulay to Modi’s digital-first governance.

✍️ Essay Spark:

“From colonial clerks to constitutional conscience-keepers — the journey of India’s Civil Services is a reflection of the nation’s transformation.”

🌱 A Thought Spark — by IAS Monk:

“True governance begins not in files, but in hearts. The civil servant is not merely a manager of schemes but a midwife of justice.”

ESSAY:

From Colonial Clerks to Constitutional Conscience-Keepers — The Journey of India’s Civil Services is a Reflection of the Nation’s Transformation

The history of India’s civil services is not merely an institutional chronicle; it is a mirror held up to the nation’s political, social, and moral evolution. From serving the British Empire as instruments of control to becoming key agents of welfare and democratic governance, India’s civil services have traversed a compelling arc. The transformation from colonial clerks to constitutional conscience-keepers underscores not only the administrative restructuring of the Indian state but also the ideological shift from subjugation to self-rule.

The Colonial Inheritance

The genesis of the Indian civil services can be traced to the administrative needs of the East India Company in the 18th century. The British, intent on consolidating their empire, crafted a bureaucratic framework that was hierarchical, impersonal, and deeply racialised. Lord Cornwallis, often regarded as the “father of Indian civil services”, institutionalised what came to be known as the Covenanted Civil Service (CCS) in the 1790s—a cadre dominated by British officers, with entry granted through nomination and later, through rigorous exams held exclusively in England.

The Macaulay Committee (1854) further entrenched this model by recommending competitive examinations based on European classics and logic, thereby limiting Indian entry. This colonial bureaucracy, particularly the Indian Civil Service (ICS), was primarily geared towards law and order, revenue collection, and maintaining British imperial interests. Indians who did make it into the ICS—such as Satyendranath Tagore in 1864—were few and were kept away from policy-making positions. Bureaucrats were expected to act as loyal executors of the British crown, not advocates of the public.

Yet, within this rigid structure emerged early debates on reform. Indian leaders like Raja Ram Mohan Roy and later the nationalist intelligentsia demanded equal access and a service more attuned to Indian aspirations. These early murmurs foreshadowed the tectonic changes to come.

Freedom and the Reimagining of Governance

With Independence in 1947, the civil services stood at a crossroads. The colonial bureaucracy had proven effective in governance but was marred by its elitism, opacity, and lack of public accountability. The newly independent Indian state, under the stewardship of leaders like Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, recognised the need for continuity but also reform.

Patel famously called the civil services the “steel frame of India” and insisted on retaining the all-India services like the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) and the Indian Police Service (IPS). He envisioned a politically neutral, professional, and meritocratic civil service that would play a stabilising role in the post-Partition chaos. Unlike their colonial predecessors, the new Indian civil servants were to be servants of the Constitution and custodians of public welfare.

The replacement of the ICS by the IAS and the establishment of the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) reflected this transition. The Constitution of India institutionalised this shift, embedding the values of impartiality, fairness, and commitment to the Directive Principles of State Policy into the service ethos. The service was no longer about tax collection and order maintenance—it was about development, justice, and participatory governance.

Developmental Bureaucracy and Nation-Building

The decades following Independence saw the civil services reinvented as a tool for nation-building. Civil servants were entrusted with implementing Five-Year Plans, expanding education and healthcare, and overseeing land reforms. They became the backbone of India’s planned economy and welfare state.

In newly carved out states and underdeveloped districts, IAS officers functioned as everything from revenue officers to educators, health administrators to election commissioners. The scope of the civil services expanded beyond administration into social engineering, often compensating for a weak political and institutional framework in a nascent democracy.

However, this also meant that civil servants wielded enormous discretionary power, which sometimes bred arrogance, inefficiency, or worse, corruption. The “mai-baap sarkar” mentality led to an administrative culture that often treated citizens as subjects rather than stakeholders.

Liberalisation and Changing Expectations

The economic reforms of 1991 ushered in a new set of challenges for the civil services. As the state moved from being a primary provider to a facilitator of services, the role of the bureaucracy also evolved. Civil servants had to adapt to a dynamic global economy, foster public-private partnerships, and deal with a more aware and demanding citizenry.

Technology, transparency, and accountability emerged as new benchmarks. The Right to Information (RTI) Act, decentralisation under the 73rd and 74th Amendments, and the rise of social audits reshaped the public’s interaction with the state. Bureaucrats were now answerable not only to elected representatives but also to an empowered civil society.

This period also saw the rise of special-purpose vehicles, mission-mode schemes, and performance-based reviews, such as the Prime Minister’s Awards for Excellence in Public Administration. While these initiatives enhanced efficiency and innovation, they also required civil servants to be agile, tech-savvy, and more participatory in their approach.

The Civil Servant as Conscience-Keeper

In today’s India, the civil servant is more than an administrator—they are a conscience-keeper of the Constitution. Whether it’s conducting free and fair elections, managing pandemics like COVID-19, or ensuring last-mile delivery of welfare schemes, civil servants are on the frontlines of governance.

Yet, challenges persist. Politicisation, red-tapism, and ethical compromises remain endemic in certain quarters. Whistleblowers have faced threats, and instances of bureaucratic inertia still haunt citizens. The need for civil services reform—training, incentives, lateral entry, and citizen engagement—has never been greater.

However, many bright examples also shine through—officers who have championed e-governance, revitalised rural schools, led disaster management with courage, or fought corruption with integrity. These are the new faces of India’s conscience-keepers.

Conclusion: A Journey in Progress

The transformation of India’s civil services from colonial clerks to constitutional conscience-keepers is emblematic of the nation’s own evolution—from colonial subjecthood to democratic sovereignty. The journey has been marked by continuity and change, pride and critique, achievements and introspection.

Today, as we mark Civil Services Day on April 21, we are reminded not only of a storied past but also of a vital future. The Indian civil servant must be a visionary and a realist, a leader and a listener, a planner and a reformer. In this demanding role, they do not merely administer policy—they animate the Republic with action and integrity.

Let this be a call to reimagine the “steel frame” as a living conscience—resilient yet responsive, firm yet fair. For in their hands rests the trust of the people, and in their service lies the strength of the Indian state.