📅 May 4, 2025, Post 6: Manipur Conflict: Where the Rivers Ran Dry: Two Years of Division, A Call for Healing | Mains Essay Attached | Target IAS-26 MCQs Attached: A complete Package, Dear Aspirants!

Manipur Conflict: Where the Rivers Ran Dry: Two Years of Division, A Call for Healing

NATIONAL HERO — PETAL 006

May 4, 2025

🧭 Thematic Focus:

• Internal Security

• Ethnic Conflict & Social Harmony

• Relief and Resettlement Policy

• Manipur’s Political & Ecological History

🌿 Opening Whisper:

“If you do not listen to the land’s many voices, you will one day hear only silence.”

🔥 Key Highlights:

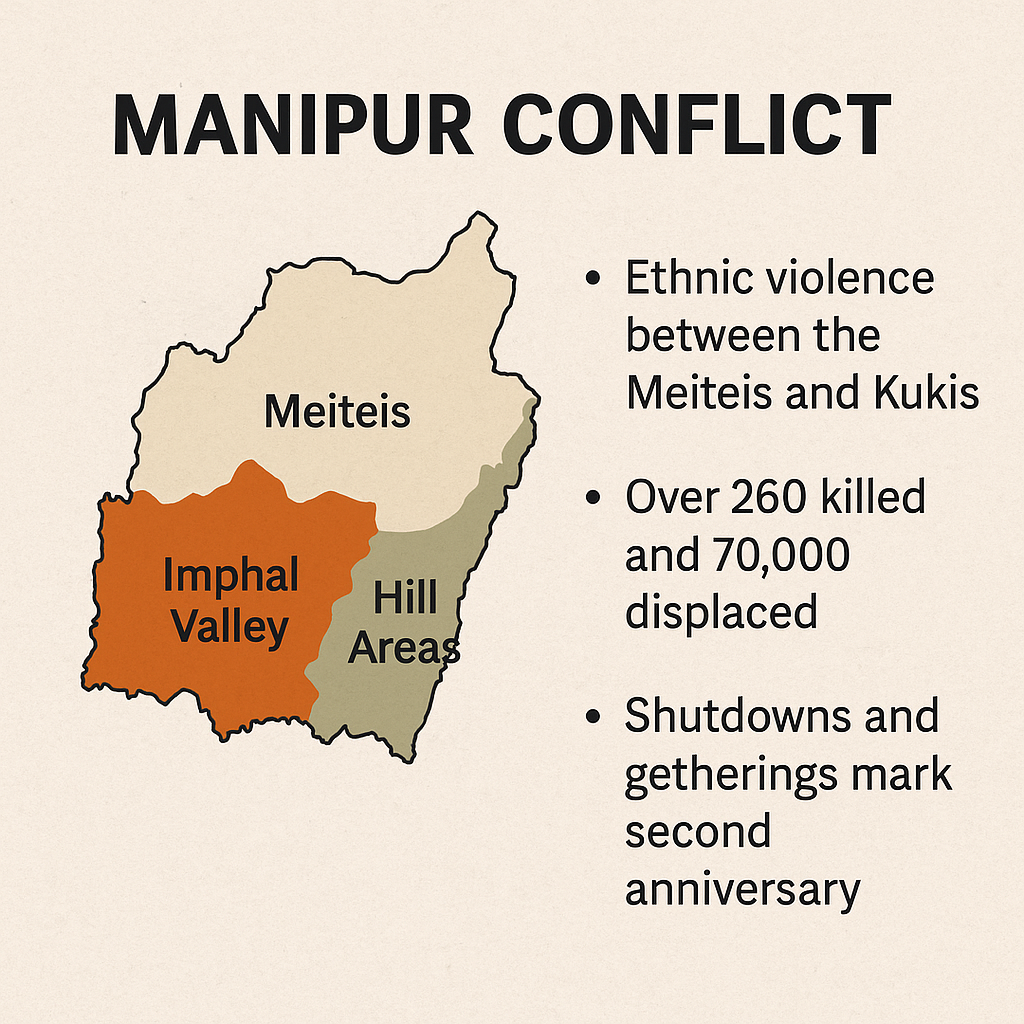

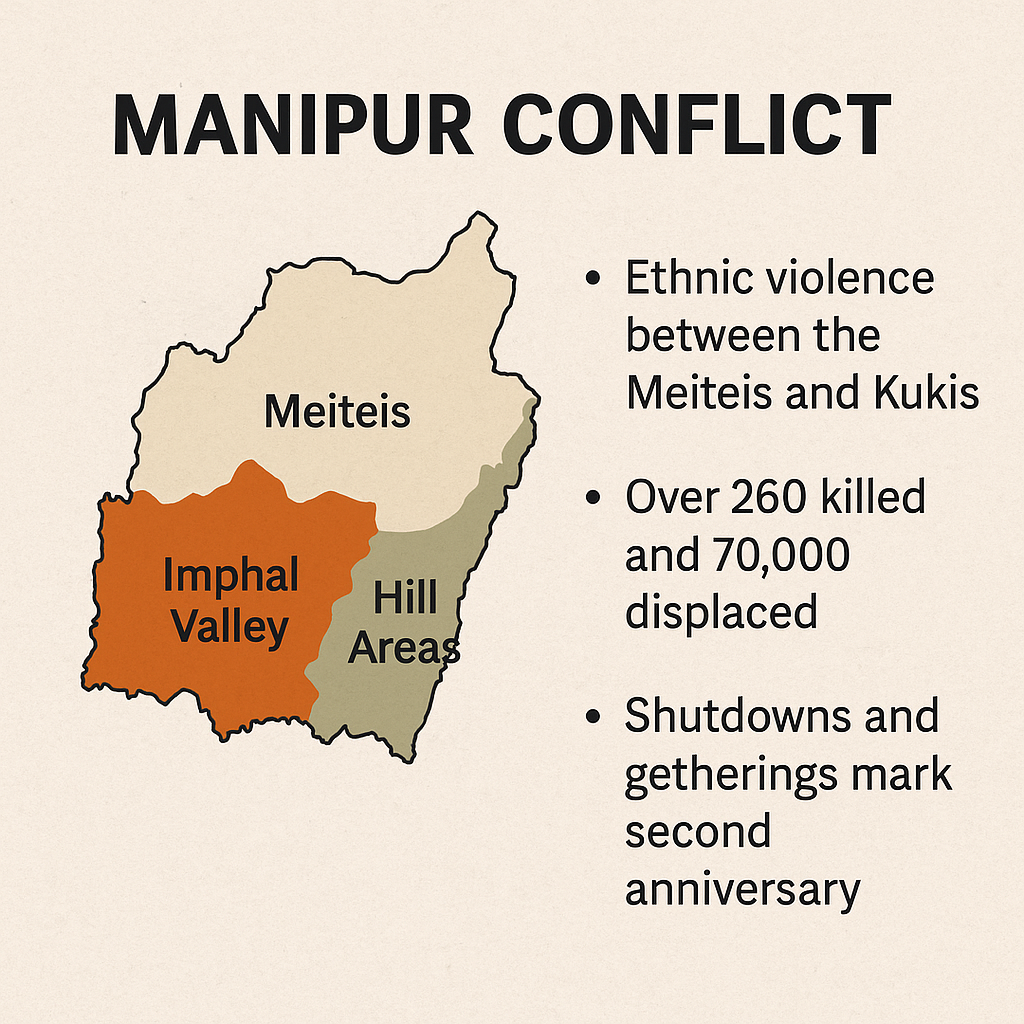

• May 3, 2025 marked two years since ethnic violence broke out in Manipur between the Meiteis (dominant in Imphal Valley) and the Kuki-Zo tribal communities (primarily in the hill districts).

• More than 260 killed, 1,500 injured, and over 70,000 displaced. Thousands remain in relief camps across both regions.

• A statewide shutdown was observed — with separate mass gatherings by COCOMI in the valley and ZSF/KSO in the hills.

• At the Manipur People’s Convention in Imphal, speakers urged the Centre to guarantee safe return and uphold territorial integrity.

• Meanwhile, in Churachandpur, ‘Separation Day’ was observed, with repeated demands for a Union Territory or separate administration for the Kuki-Zo regions.

• Across Manipur and cities like Delhi and Bengaluru, events reflected the continuing geographic, emotional, and administrative divide.

• No concrete breakthrough has occurred; political dialogue between communities remains stalled.

📘 Concept Explainer:

Who Are the Meiteis and Kukis? A Brief Historical Context

• Meiteis form the dominant community in Imphal Valley, primarily Hindu Vaishnavite, with historical kingship records, martial traditions, and rich literary-cultural heritage (Puya texts, Sankirtan, Ras Lila).

• Kuki-Zo communities are Christian tribal groups, residing mainly in the hills, with a legacy of autonomy, oral history, and resistance (e.g., Kuki Rebellion of 1917–19 against British rule).

• Both groups were historically segregated by terrain, with minimal socio-cultural intermingling. Land, forest rights, and governance systems have long been friction points.

• The conflict reignited in May 2023 after clashes over ST status demand by Meiteis, eviction drives in forest areas, and populist mobilisations by community groups.

🌱 Pathways to Peace: Key Issues & Imperatives

• Lack of Dialogue: Civil society leaders met in Delhi under MHA supervision, but no resolution emerged. Deeper issues of mistrust remain.

• Relief Camps & Displacement: Over 70,000 remain displaced, surviving on ration and minimal cash support. Many areas remain unsafe for return.

• Demand for Union Territory: The Kuki-Zo communities seek administrative autonomy, citing decades of exclusion and now irreconcilable differences.

• Territorial Integrity Stance: Meitei organisations oppose any division, calling for restoration of state unity.

• Environmental Triggers: Deforestation, drying springs, and conflict over forest land worsened mistrust. Ecological degradation fed the crisis.

• Youth Radicalisation: Hundreds of youths were armed or indoctrinated, making reconciliation harder with every passing month.

• Drug Economy & Corruption: Underlying issues like poppy cultivation, timber mafia, and state corruption compound the tension.

📌 GS Paper Mapping:

• GS Paper 1 – Indian Society: Ethnic conflicts, tribal identity, social cohesion

• GS Paper 2 – Governance: Centre-State relations, Internal security mechanisms

• GS Paper 3 – Internal Security: Ethnic insurgency, relief camps, borderland instability

• GS Paper 4 – Ethics: Public accountability, justice, leadership in conflict zones

🪶 A Thought Spark — by IAS Monk:

“You cannot plant peace in scorched earth — it must be sown where memory meets forgiveness, and watered by truth.”

High Quality Mains Essay For Practice :

Word Limit 1000-1200

Manipur’s Wound, India’s Mirror: Understanding Ethnic Conflict and the Philosophy of Division

In the far corners of India’s northeast, nestled in the folds of mist-covered hills and verdant valleys, lies Manipur — a state as culturally rich as it is historically fragile. On May 3, 2023, this fragile balance shattered when long-simmering tensions between the Meitei and Kuki-Zo communities erupted into widespread ethnic violence. Two years later, over 260 lives have been lost, 1,500 injured, and 70,000 displaced. Yet beyond the statistics lies a deeper tragedy — of identities wounded, trust fractured, and a future that stands at a moral crossroads.

To understand the Manipur conflict is not merely to chronicle a series of violent events. It is to confront the deeper question: why do ethnic groups fight? Why do neighbours, bound by shared geography and decades of coexistence, turn against each other with such vengeance? And more importantly — how can they heal?

The Anatomy of a Fracture: Manipur’s Ethnic Divide

At its core, the Manipur conflict stems from a struggle over land, identity, and power. The Meiteis, largely Hindu and settled in the fertile Imphal Valley, form the demographic and political majority. The Kuki-Zo tribal groups, predominantly Christian, reside in the surrounding hills. While geographically segregated, their lives and economies have been historically intertwined.

Tensions escalated when Meiteis demanded Scheduled Tribe (ST) status — a move opposed by the tribal communities who feared encroachment into protected hill lands. Parallel issues — such as forest eviction drives, crackdowns on poppy cultivation, and suspicion over illegal immigration — acted as catalysts. Community groups mobilized, distrust deepened, and social media became a weapon. What followed was a spiral of mob violence, arson, and displacement, affecting both communities indiscriminately.

In the aftermath, relief camps replaced villages, and demands for separate administrations emerged — with Kuki-Zo leaders calling for a Union Territory status, and Meitei groups insisting on the territorial integrity of Manipur. As political leaders vacillated and administrative silence deepened, civil society attempted, and largely failed, to bridge the chasm.

Beyond Borders: The Universal Roots of Ethnic Conflict

The Manipur crisis, though local in its setting, is universal in its themes. Across history — from Rwanda to Bosnia, from Assam to Northern Ireland — ethnic violence has followed a disturbingly similar pattern.

At the heart of most ethnic conflicts lies three driving forces:

- Fear of Extinction: When communities perceive a threat to their existence — cultural, political, or physical — they resort to aggression. It is not just the fear of being killed, but the fear of being forgotten, of being erased from history.

- Narrative of Historical Grievance: Ethnic groups carry long memories — of colonization, betrayal, oppression. These become identity myths, shaping generations. In Manipur, the legacy of British policies that segregated hills and valleys still echoes. The absence of a shared history has created isolated silos of memory.

- Scarcity of Resources and Representation: Whether it is land, jobs, forest rights, or political posts — perceived inequities often sharpen group consciousness. When the state is seen as biased or indifferent, groups seek autonomy or secession.

But the most dangerous weapon in ethnic conflict is othering — the dehumanization of “them” by “us.” When people cease to see neighbours as humans and begin to see them as threats, no constitution, no army, no peace accord can hold back the blood.

Philosophical Reflections: Why We Fight

From a philosophical lens, ethnic violence is a failure of imagination — the inability to imagine another’s pain as one’s own.

As Jiddu Krishnamurti said, “When you call yourself an Indian or a Muslim or a Christian or a European… you are being violent. Because you are separating yourself from the rest of mankind.”

Ethnic identity, in essence, is a social construction, not a biological destiny. But it becomes lethal when politicized, mythologized, and weaponized. When identity is used not as a source of belonging, but as a wall to keep others out — it breeds conflict.

Beneath every act of ethnic violence is a philosophical rupture — the collapse of the idea that humanity is one. Manipur’s hills and valleys are not just divided by geography, but by epistemology — by what people believe to be true about each other.

Healing Manipur: Roads Beyond Revenge

The healing of Manipur must begin with truth — not just legal facts, but emotional truths. What do displaced mothers feel? What do young boys trained in violence now believe? What stories are being told in camps, schools, and kitchens? Unless these stories are heard and held, reconciliation cannot begin.

A few crucial steps can pave the way:

- Dialogue Without Preconditions: Leaders from both communities must sit across the table — not as adversaries, but as wounded parts of the same body. Silence breeds rumours; dialogue builds bridges.

- A Common History Project: A shared curriculum that includes the histories of both Meiteis and Kukis must be created. Children must know each other’s songs, struggles, and saints — not just their scars.

- Ecological Restoration as Reconciliation: Many flashpoints began with land use conflicts. Reviving springs, forests, and sustainable agriculture can create joint projects where communities work side by side.

- Rehabilitation with Dignity: Relief camps are not homes. Safe resettlement, livelihood opportunities, and mental health support must be prioritized.

- Countering Hate with Ethics: Local youth must be engaged through community ethics workshops, storytelling, art, and sports — building empathy across the divide.

The Role of the State and Civil Society

The Union government must move beyond knee-jerk security responses and create a time-bound roadmap with independent monitoring. Civil society groups, religious leaders, and women’s organisations must be empowered to become agents of trust.

A model similar to South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission can be adapted — where forgiveness is earned, not demanded.

Conclusion: From Wound to Wisdom

The Manipur conflict is not just a state’s tragedy — it is a mirror to the nation. It shows how quickly the illusion of harmony can collapse when institutions falter, and identity becomes ideology.

But it also holds hope. Every tear shed in a relief camp, every child born amidst ruins, every hand that still dares to reach across the divide — is a reminder that healing is possible.

Philosophy teaches us that division is a mental construct. The map of Manipur may be split today, but the rivers do not know borders, the forests do not choose sides, and the children — they still dream of peace.

Let us listen to those dreams.

Closing Quote:

“Peace begins when we stop asking who is to blame, and start asking how we can hold hands again.” — IAS Monk

Target IAS-26: Daily MCQs : May 4, 2025

📌 Prelims Practice MCQs

Topic: Manipur Conflict

📘 MCQ 1: Ethnic Composition of Manipur

Which of the following statements accurately describes the ethnic composition of Manipur?

•1) The Meiteis primarily reside in the hill districts of Manipur and are mostly Christian.

•2) The Kuki-Zo communities predominantly live in the hill areas and practice Christianity.

•3) The Meiteis are largely concentrated in the Imphal Valley and practice Hindu Vaishnavism.

•4) Both Meiteis and Kukis share equal land and political representation in Manipur.

A) Only two

B) Only three

C) All four

D) Only one

🌀 Didn’t get it? Click here (▸) for the Correct Answer & Explanation

✅ Correct Answer: A) Only two

🧠 Explanation:

•1) ❌ Incorrect. The Meiteis reside in the Imphal Valley, not the hill districts, and are primarily Hindu Vaishnavites.

•2) ✅ Correct. The Kuki-Zo communities are predominantly Christian and live in hill districts.

•3) ✅ Correct. The Meiteis are concentrated in the Imphal Valley and are mostly Hindus.

•4) ❌ Incorrect. Political and land representation is not evenly distributed, with Meiteis holding greater influence.

Hence, statements 2 and 3 are correct.

📘 MCQ 2: Triggers and Fallout of the 2023–25 Manipur Conflict

Which of the following were key triggers or outcomes of the ongoing ethnic conflict in Manipur?

•1) Displacement of over 70,000 people and deaths of more than 260.

•2) Meiteis’ demand for Scheduled Tribe (ST) status.

•3) Violent evictions of forest settlers in the hill districts.

•4) Granting Union Territory status to the Kuki-Zo areas.

A) Only two

B) Only three

C) All four

D) Only one

🌀 Didn’t get it? Click here (▸) for the Correct Answer & Explanation

✅ Correct Answer: B) Only three

🧠 Explanation:

•1) ✅ Correct. Over 70,000 displaced and 260+ killed since May 2023.

•2) ✅ Correct. The ST demand by Meiteis was a major flashpoint.

•3) ✅ Correct. Eviction drives in forest areas added fuel to the fire.

•4) ❌ Incorrect. No Union Territory status has been granted yet — it remains a demand.

Hence, statements 1, 2, and 3 are correct.

📘 MCQ 3: Philosophical Insights from the Conflict

Which of the following statements reflect philosophical insights into ethnic conflict as discussed in the essay?

•1) Ethnic violence is often rooted in fear, perceived injustice, and absence of shared narratives.

•2) Conflict begins when cultural differences are acknowledged with mutual respect.

•3) Shared ecological projects and history-building can foster reconciliation.

•4) Ethnic identities are biological truths that inevitably lead to group clashes.

A) Only two

B) Only three

C) All four

D) Only one

🌀 Didn’t get it? Click here (▸) for the Correct Answer & Explanation

✅ Correct Answer: B) Only three

🧠 Explanation:

•1) ✅ Correct. The essay discussed fear of extinction, grievance, and narrative gaps as root causes.

•2) ❌ Incorrect. Mutual respect does not cause conflict — it prevents it.

•3) ✅ Correct. Ecological restoration and common history were proposed as healing tools.

•4) ❌ Incorrect. The essay clearly noted that ethnic identities are social constructs, not biological determinism.

Hence, statements 1 and 3 are correct.